This article is also in audio form for your enjoyment. Scroll down just a bit to find the recording.

Learn how to support solitary bees and create a home for the native bee populations in your area. Find some important solitary bee hive instructions, support pollinators and boost your plant health.

Solitary bees are quickly becoming the new bee to host in your yard. One of Mother Nature’s best pollinators, they’re gentle, easy to care for, and critical pollinators for food and ecosystems. Unlike the social honeybee, solitary bees live and work alone, and they also don’t make honey. They forage for their own food and find their own nests, and all females lay their own eggs. Solitary bees make up the largest percentage of the bee population — out of the more than 20,000 bee species worldwide, around 90 percent are solitary!

Two popular bees to host in your yard are mason bees (Osmia spp.) and leafcutter bees (Megachile spp.). About 140 species of mason bees and 242 species of leafcutter bees inhabit North America, many of them native. Before honeybees were brought over from Europe, native bees pollinated the continent, enriching their habitat and helping it grow.

Audio Article

Springtime Is for Mason Bees

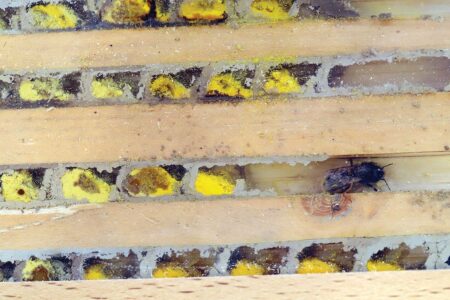

Mason bees are spring pollinators and emerge from hibernation in early spring when temperatures reach about 55 degrees Fahrenheit. They seek pollen and nectar after their long winter slumber, and they’ll stay within 200 to 300 feet from where they emerged for the duration of their life. Mason bees get their name because they use mud for their masonry work when constructing their nests. Their mandibles aren’t strong enough to cut wood, so they search for natural holes, such as hollow stems, holes in wood caused by insects, or nesting shelters hung up by gardeners or farmers. Once a female mason bee has found her nesting cavity, she’ll seal the end with mud and build a series of chambers that each include an egg, a pollen loaf (a ball of pollen mixed with nectar), and another mud wall to separate the chamber from the others. She’ll repeat this about seven times in each nesting cavity. Each egg will hatch into a larva and consume the pollen loaf. It’ll then spin a silken cocoon and form into a pupa. While it hibernates over winter, it grows into an adult bee and then emerges the following spring and repeats its life cycle. A female mason bee will lay about 15 eggs in her lifetime, and both males and females will die 4 to 6 weeks after emerging.

One popular type of mason bee that farmers and gardeners are using in the Pacific Northwest is the blue orchard mason bee (O. lignaria). Often mistaken for houseflies, they sport a greenish, iridescent sheen on their backs and are usually spotted in gardens covered in pollen. In the Midwest and on the East Coast, gardeners can host horn-faced mason bees (O. cornifrons), which have tan and fuzzy bodies.

Summers with Leafcutter Bees

Leafcutter bees begin to emerge when temperatures are a consistent 75 degrees or higher for about two weeks. Like all solitary bees, they, too, find their own cavity in which to lay their eggs. A female leafcutter bee will lay about 30 eggs in her lifetime, which ranges between about 4 to 6 weeks. She’ll start cutting tiny crescent-shaped pieces out of leaves or flower petals (without harming the plants). Then, she’ll fly those pieces back to her nest, where she’ll chew them until they become pliable and then push them up along the walls of the cavity. The female will then lay an egg and leave a pollen loaf for her baby before wrapping up the leaf chamber and making a cozy little “sleeping bag” around the egg. This process can sometimes take her up to five hours. The egg will hatch into a larva, which will then consume the pollen loaf. Unlike a mason bee, a leafcutter larva doesn’t weave a cocoon. Instead, it’ll overwinter in its sleeping bag and emerge as an adult bee the following summer.

Do They Sting?

Mason bees are known not to sting, because they don’t have a hive to protect. Males don’t have stingers, and females will only sting if trapped or squeezed. If you accidentally incite one to sting you, it’ll feel more like a pinch or mosquito bite. There are also no recorded allergic reactions to mason bee stings.

Belly-Flopping Pollinators

Mason and leafcutter bees are incredible pollinators. They have a special way of collecting pollen — they belly-flop onto blossoms! Honeybees and bumblebees have pollen baskets called “corbiculae” on their legs, while mason and leafcutter bees have tiny, sticky hairs called “scopae” on their abdomens. When they collect pollen, they belly-flop onto the blossoms, and the pollen sticks all over their bellies. They then carry the pollen to other flowers. This enables them to have a 95 percent pollination rate, compared with honeybees, which have a 5 percent pollination rate. Solitary bees can visit more than 2,000 blossoms a day, which is why they’re known as one of our most efficient and critical pollinators.

Mason and leafcutter bees aren’t picky; they’ll collect pollen and nectar from just about any plant that’s blooming. Not only do they help us grow more food, but they also pollinate our native plants. Pollinated trees and plants grow bigger and stronger than unpollinated ones, which in turn strengthens soil, provides cleaner air, feeds other wildlife, and boosts the overall health of our ecosystems.

A Bee-autiful Partnership

One-third of the food we eat is directly pollinated by bees and other pollinators. Farmers use bees to pollinate their crops and grow more food. Solitary bees excel at pollination, so when farmers use mason or leafcutter bees in partnership with honeybees, they see an increase in their yields.

Honeybees are overworked in the pursuit of keeping up with our high demand for food. By using more solitary bees on our farms, we can lessen the stress on honeybee populations and utilize the amazing hardiness of solitary bees to keep our grocery stores stocked with fruit.

Create a Habitat for Solitary Bees

Solitary bees are easy guests to host in any yard, with a generous return on investment in the form of maximum pollination. First, decide whether you’d like to create a habitat for mason bees in spring or leafcutter bees in summer (or both), and then gather your materials. Here are some recommended supplies and best practices for a successful habitat:

Supply food.

After solitary bees emerge, they’ll be hungry! Talk to your local garden nursery to learn what blooms in early spring and summer for your area, or find resources online, such as the National Wildlife Federation’s “Gardening for Pollinators” article.

Provide shelter.

Set up a solitary bee house with a roof or cover to protect the nesting material from getting wet. Hang the house in morning sun. Insert proper nesting material to ensure your bees remain healthy all year long. Stacking trays or tubes that can be opened and separated are the best nesting material for bees. Do not use bamboo reeds or holes drilled in wood (see “Clean every fall”). Mason bee nesting holes are larger than those of leafcutter bees, so make sure you use the correct ones.

Offer mud or clay.

Mason bees use mud or clay soil to plug their holes and lay their babies. Dig a hole about 50 feet away from their nests, and stir in a mixture of mud and clay. Make sure it remains damp throughout the season.

Don’t use pesticides.

Weedkillers and pesticides can harm all our pollinators. Remember that mason bees build with mud to house their babies, so any pesticides can kill developing larvae. You can find many nontoxic gardening tips online for maintaining a beautiful garden without the use of pesticides.

Clean every fall.

This is one of the most important steps in hosting your own solitary bees. You must harvest and clean mason bee cocoons and sterilize their nesting blocks every fall to remove predators. Bamboo reeds or holes drilled into wood can’t be opened and cleaned at the end of the season, which means mold, fungus, and predators (such as Houdini flies or pollen mites) could wipe out your solitary bees.

Many people like to host their own mason bees in their backyards and take care to clean their habitats every fall. However, if you want the benefit of pollination without the hassle of cleaning the cocoons and sterilizing nesting blocks, you can rent your bees from Rent Mason Bees, and they’ll provide you with everything you need to host and pollinate your yard, including cleaning and hibernating services.

When solitary bees show up, success literally blooms all around. With a little research and preparation, you can bring bountiful pollination and a healthy ecosystem to your property — not to mention some fun for you and your family — by providing a home for these valuable insects.

Thyra McKelvie runs the pollination program at Rent Mason Bees to help gardeners host solitary bees. Her passion is to educate and teach more people about solitary bees and the importance of taking care of all our pollinators.