What is timber frame construction? Construct a tried-and-true timber frame using timber framing joints in this how-to, complete with helpful tips.

Traditional timber framing looks great, and is very strong and durable. Although it takes time to make a mortise and tenon joint and secure it with a wooden peg (treenail), the sense of pride and accomplishment is well worth the effort. This is the way buildings were made for centuries, by carpenters using simple hand tools–mainly a saw, mallet and sharp chisel.

Many people, even professionals, confuse timber-framing with post & beam construction. Both methods use heavy timbers, which accounts for the confusion that exists between the two. Traditional timber-framing uses difficult-to-make mortise & tenon joints secured with wooden pegs (tree nails), whereas post & beam often uses simple lap joints and even metal fasteners to hold the pieces together. Various materials have been used to fill between the timbers, such as wattle and daub (sticks and mud), bricks, stucco and straw. Timber-frame structures can be finished off in numerous ways, just like a modern stick-built house–among them, plywood, clapboard, board & batten, shingles, or even stucco. Today, houses are generally stick built with 2×4s or 2×6s, and sheathed with plywood to stiffen the frame and keep it from racking.

Tips to make timber framing easier:

How to Build a Timber-Frame

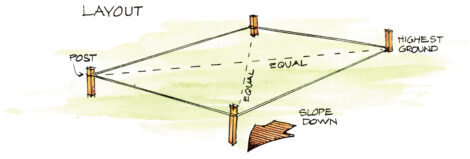

Lay out the shed with mason’s string and four wooden stakes. Use a level and check the diagonals for square.

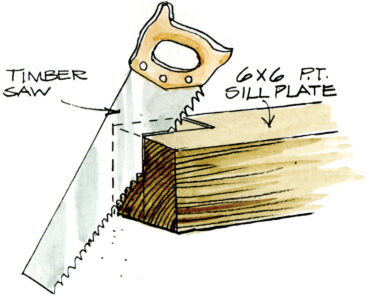

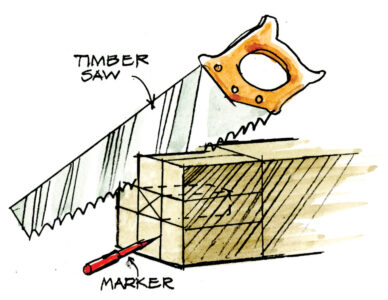

Cut lap joints on the ends of the 6×6 pressure- treated sill beams, using a coarse-cut timber saw. Set out the base, level and square, on concrete blocks.

With a framing chisel, cut 2″×2″ mortises through the lap joints (remembering that the corner posts are 5″×5″). Place a piece of wood under the mortise to avoid splitting out, and turn the beam over to finish the cut from the other side. Use a carpenter’s square to make sure the sides of the mortise are straight.

Use 4×6 pressure-treated lumber for the floor joists, set into 2″-long×3″-deep pockets in the sills. Cut a 35-degree bevel at the ends of the joists to alleviate stresses as timbers expand and contract.

Cut tenons on each end of the 5″×5″ corner posts, by making rip cuts a little wide of the mark and paring them down to fit the mortises. On all tenons, chamfer the edges with a sharp chisel or a rasp to make assembly easier.

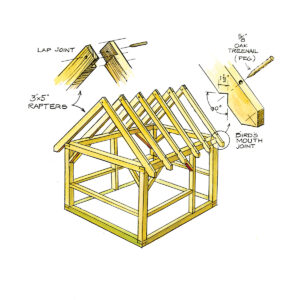

Make the lap joints on the top plates, and set them upside-down on the sill beams while you mark, cut and fit the studs, braces and girts. The 4″×4″ braces should be fastened with oak pegs (treenails or “trunnels”) passing right through the posts. Drill the holes carefully, from both sides.

Cut lap joints in the tops of the 3″×5″ rafters, and cut bird’s-mouth notches where they will rest on the top plates. Mark the exact location by laying trial pieces on the floor. Use the first rafter as a pattern for all the rest. Cut the rafter tails long enough to deflect rainwater, but make sure there is enough clearance for the door (if it is to open outwards). Use treenails at the lap joints and at the top plates.

Once everything fits, mark and cut corresponding mortises in the sill plates for the 3″×5″ studs, then gather your army of helpers to raise the building. It can be tricky to fit the girts and braces at the same time–you may find it easier to assemble an end wall (or “bent”) on the base first, lift it into place and repeat the procedure at the other end, before fitting the other two walls and locking them all together with the final top plates. Nail the bents to the sills with temporary diagonal braces until the walls are finished. Assemble the rafters, and nail a temporary ridge board to the peaks until you are ready to enclose the building.

More from Backyard Building:

• How to Build a Rustic Gate

• How to Build a Classic Cottage Garden Shed

Reprinted with permission from Backyard Building by Jeanie and David Stiles and published by The Countryman Press, 2014.